Suchen und Finden

Mehr zum Inhalt

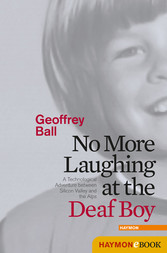

No More Laughing at the Deaf Boy - A Technological Adventure between Silicon Valley and the Alps

Kingsgate Drive

A stream begins

Beneath a stone

Water flows

The path well known

Over and over

Again and again

To repeat the path

Never to end

The best street in the whole world to grow up on was Kingsgate Drive, located on Sunnyvale’s south side near Serra Park and Serra Elementary School. Like many other people, I recall my childhood home with great affection – and with good reason. In 1969, Sunnyvale had approximately 50,000 residents living mostly in single-story suburban style homes intermingled with vast tracts of apricot, pear and cherry orchards and a few acres of flowers. The main boulevards were Sunnyvale Saratoga Road to the east, Homestead Road to the south, Fremont Road to the north, and the finished portion of Highway 85 to the west. Serra Park, with its fine man-made creek and amazing steamship play boat complete with steering wheel, was a short walk away, and Serra Elementary school was adjacent to the park.

From 1969 through the 1970’s Sunnyvale was in its hey-day. Moffet Field Naval Air Station, originally built as an airstrip for dirigibles, had been the genesis of a key research and development hub for NASA, Lockheed Space and Missiles, Northrop, and many others. The development of the transistor eliminated the need for vacuum tubes, and the defense industry was in its prime, driven by the close proximity of Onizuka Air Force Base, the “Blue Cube,” and the cold war-era thirst for high technology and cutting edge electronics. Hewlett Packard was arguably the dominant player in the Valley’s booming electronics industry. These were the days before the area was known as Silicon Valley. Sunnyvale was already a mecca for electronics engineers, and any engineer worth his salt, such as my father, was dying to land a position in the Valley. The power of the electronics industry drew top engineers from around the globe, so the Ball family became good friends with people like the Camenzinds (from Switzerland), the Siggs (also from Switzerland), and their friends the Heinemanns (from Germany). The Valley was attracting the best and the brightest from all across the globe, and our community was a truly multicultural one.

The impact of Stanford University on the development of Silicon Valley cannot be overstated. Stanford was a hubbub of activity, and many Saturdays found my father and me walking around the campus, looking at all the activity both inside and outside the labs This was back in the days before security was all that it could be, so it was no problem to stroll around and see students and researchers working on their projects. My father and I would spend hours upon hours in the Stanford libraries and at the bookstore, where my father found and read the latest integrated circuit and electronics publications. Stanford was truly alive then, and the place was electric with energy. In the early 70’s, it was really quite the sight to see. I was mesmerized by all those long-haired hippie students making the incredibly magical devices and inventions on display, many of which were glimpses into the future.

The demand for a highly educated workforce exceeded the levels that Stanford and nearby San Jose State University could supply. The exploding electronics industry and their supporting fields and services desperately needed new employees in order to grow. De Anza and Foothill junior colleges became key factors in training and educating new workers for the fields of electronics engineering, manufacturing, mechanics and computer technology. Again, in the early 1970’s these institutions were places where innovation was in the air. “De Anza days,” when the entire campus was thrown open to the public for the weekend, allowed students to showcase their latest achievements. We never missed these epic technology demonstration events, which comprised everything from arts and crafts to the forerunners of modern digital computer games, including a computer connected to a black and white display screen that would play endless rounds of tic-tac-toe and never lose. Other devices on display, including a working seismograph that recorded the shocks of the San Andreas Fault earthquakes, were a source of fascination to most of us. I think we were more interested in understanding earthquakes than we were afraid of them, since anyone who lives in Sunnyvale for more than a year or two is sure to feel at least a couple of good rollers.

Kingsgate was swarming with the sons and daughters of the techies who turned Silicon Valley into what it is today. The families of Kingsgate were a wide cross-section of the Valley at the time. We had several neighbors who worked in the defense and aerospace industries, electronics, real estate, or law, as well as a grocer and a lawn-sprinkler installer. And most of them had lots of children. The Banker family two doors down from us had four daughters; the Stevensons next door to them had three, and the Schenones beside them had four daughters and a son, so just those four families on Kingsgate had 15 kids, counting me and my brothers. Kingsgate was a very small street linking Dallas to Lewiston, yet in 1970, from end to end, there were 47 school-age children in 22 homes. There was no shortage of playmates – or of potential babysitters. My favorite was Erin O’Conner, who took me under her wing and helped me out all the way through high school by giving me advice and pointers along the way.

When the moving van carrying my family’s belongings pulled into the big driveway of 1526, it was the greatest arrival I could have imagined. It seemed like everyone on the entire street came out to watch. We had only had a small two-bedroom apartment in Massachusetts, so could not have taken the movers too long to unload and carry all of our possessions into 1526, yet somehow they made a day of it anyway. By the time they were done, I had met Matt Schenone, who by day’s end would be my new “first best friend.”

The very first week we lived in the salmon-colored house smack in the middle of Kingsgate, my brother and I realized that although our house may have been pink and may have had a purple car in the driveway, it had one thing going for it: It was a magnet for all the kids on the street. There were several reasons for this, the first being that we had the widest and flattest cement driveway – perfect for roller skating, bike turnarounds and dodge ball. The Schenones also had a large driveway, but theirs was blocked by an old Dodge that Mr. Schenone was always going to fix up some day but never did (he had it towed away years later).The fact that they had converted their garage into an extra room for the two older girls meant there was no garage door suitable for “wall ball.” If our home had a redeeming factor, it had to be the backyard, which was small but had everything else going for it.

The previous owner of 1526 had somehow acquired from the Sunnyvale Parks and Recreation department the old jungle gym (a. k. a. monkey bars) and swing set that had been in Serra Park before it got new playground equipment. Having proved too large for the previous owner to move, both this huge climbing structure and the swings were in our new backyard. Unlike store-bought play park equipment, this was real heavy duty gear. Our predecessors had also left behind a small outdoor goldfish pond chock full of fish and lily pads. To top it off, there was a large crabapple tree in our yard that turned out to be the favorite climbing tree in the neighborhood. A kid could climb way up into the branches and then toss “crabapple bombs” on moving roller skating targets on the driveway below. Every morning when my brother and I woke up, we would be inundated by a horde of kids coming over to play. We skipped the awkward new kid phase and immediately became the “rock stars” of Kingsgate because we lived in such a great house, even if it was pink or salmon or whatever. It was the best.

Matt Schenone soon had me running his football games. He would always yell out, “Quarterback! Called it first!” (he always called it first), but I was always quite happy to be his wide receiver and sometimes running back, even though I had no clue what those terms really meant. Soon Matt and I had progressed to a level where we could take on the big kids up the street. Joe Walker and Kent Bates, who were both older than we were and two grades ahead of us, would team up against Matt and me. We always got trounced soundly as we could not really do much to “Big Joe,” who was twice our size and could throw the ball much better than we could. Kent was not as much of a football talent as Joe was, but he was faster than we were. Joe also knew all the strange and baffling rules of American football, and since Matt and I were younger, it was no use to protest against Joe’s rulings. If I snapped the ball back to Matt and somehow got open and caught Matt’s pass and ran it in for what we thought was a touchdown, Joe would invariably come back with a penalty call such as, “Ruling! Ruling! Receiver interference on the defender past the ten yard line. Five yard penalty. Lose a down!” In the 273 matches that we played against Joe and Kent, Matt and I had a record of one win and 272 losses. They were nice enough to let us win one game on Matt’s birthday.

Matt lived three doors down from us on Kingsgate. He had four older sisters, and his father was a real estate agent. Tony Schenone and his co-worker Mrs. O’Conner, who also lived on Kingsgate four doors down from 1526, had sold much of the real estate in the southern Sunnyvale area. Mrs....

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.