Suchen und Finden

Mehr zum Inhalt

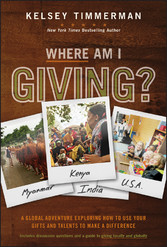

Where Am I Giving: A Global Adventure Exploring How to Use Your Gifts and Talents to Make a Difference,

Introduction

The Trash Picker, the Slave, and the Garment Maker (The World, 2001–2018)

One of the most beautiful sights I've seen is an 11-year-old girl laughing in the worst place I've ever been.

She haunts me to this day.

Smoke and stench – fire and brimstone – surrounded her as she threw her head back, shoulders shaking. Her eyes closed to the hellscape of Phnom Penh's municipal dump. She had been sifting through previously picked-through trash looking for something of value. Treasure or trash? Discard or keep?

She and the other children earned a dollar per day, if they were lucky, by selling their findings while their parents picked through fresh trash brought by a parade of garbage trucks. Most of the trash pickers were former farmers.

What must have life been like back on the farm?

“Life in our village is tough,” I imagined the parents saying. “Farming is no way to make a living. I hear there's this garbage heap in the city where we could work and even the kids could earn a dollar per day.”

They packed up their belongings and moved to the city. My hell on earth was someone else's opportunity.

That thought coupled with the sight and the smell of the dump made me physically ill. I had to fight from puking. I didn't want them to see that what they did and where they did it disgusted me.

Until visiting the dump, I didn't realize that people lived in places like this.

The adults wore rags across their noses and mouths, their vacant, almost lifeless eyes searching through the trash.

But the girl …

The girl still had life and light in her eyes (see Figure I.1). I wanted to do something. I wanted to grab her hand, walk her away from the dump, and give her … an education? A chance? A future? But there were hundreds like her in this one dump.

Figure I.1 The girl at the Phnom Penh dump (Cambodia, 2007).

What could I do? We live in a world where 1.2 billion people live on less than $1.25 per day. Where half the world's population lives on less than $2.50 per day.1 Where 21% of American children live in poverty.2 I was just one man, researching my first book, traveling on my second mortgage. And she was just one girl.

I pulled out my Frisbee and tossed it to her. She threw it to a barefoot boy, who put down his burlap bag of trash treasures to catch it. I taught them how to throw a Frisbee and for 15 minutes we escaped into a world of throwing and catching, of laughing and smiling. Then they got back to work and I went to my $11 per night guesthouse and showered three times until the stench of the dump lingered no more.

But no amount of scrubbing could wash away the memory of the dump. Are awareness and empathy treasures that can enhance our lives? Or are they burdens that would be better off discarded because awareness without action leads to guilt and apathy?

When do we act? How do we act to make a positive difference?

I was faced with this same dilemma a few years ago when I traveled to Ivory Coast to meet cocoa farmers while researching my second book.

I never expected to meet a slave in my lifetime, but then I met a man named Solo who showed me a view of another world. He was from the neighboring country of Ghana and had followed false promises to a cocoa farm. He had asked to leave, but wasn't allowed to go. He told me the donkeys got treated better than he did because at least they were fed when they weren't working. He told me they do worse things to him than beat him. Solo called the guy he worked for “master.”

For me hearing a human being call another human being “master,” in this day and age, shook me to my soul. I knew modern slavery existed, but knowing about it and witnessing it were two completely different things. Sitting next to Solo, a living breathing slave and listening to his story, I felt compelled to act, to help, to make a difference.

I hatched a plan where I hired Solo as my translator away from the farm for the day. It worked.

At the end of the day, I paid Solo $40 and asked him where he wanted to go.

“Home,” he told me. “To Ghana.”

Solo's master figured out what was going on and sent me a text, threatening to have me arrested. Solo was trying to figure out a way home when we got separated.

But the slave …

Days later I learned Solo was back on the cocoa farm. Was he captured and taken back? Maybe. But it's more likely that he looked at the opportunities before him and chose to go back. Solo chose slavery.

When I learned Solo was back on the farm, I worried what repercussions he may have suffered from my actions. I acted. I did something, but I wish I had done nothing. Good intentions aren't enough; it's the results those intentions produce that matter.

I regretted not acting to help the girl at the dump. I regretted helping Solo.

I was a recent college grad when I met the man who made my favorite T-shirt outside the factory in Honduras where he worked. It was awkward. The T-shirt cost nearly as much as a day of his labor. There I was, skipping around the globe, and there he was in a sea of workers with a chain link fence and a long workday at his back, kind enough to stop and chat with me, puzzled as the security guard at the front gate had been.

Why was I there?

A degree in anthropology had inspired my curiosity and I left the flat fields of the Midwest to meet people who lived differently than I did. I'd save up money working a retail job or as a scuba instructor, and then I'd blow it all traveling. I started to write about my travels and would get paid a whopping $10 from publications for stories like spending the night alone in Castle Dracula in Romania. I could go anywhere in the world and have adventures worth writing about. It was the world's most expensive hobby.

I was looking for that next place to go, and my favorite T-shirt had a funny picture of a guy from a TV show in the early 1980s and these words: “Come with me to my tropical paradise.” “So,” I thought, “why not?” I put on the shirt and showed up at the factory half expecting the factory management to laugh at the randomness and silliness of it all and throw open the factory gates. They didn't, so I waited to the side of the factory to meet someone who possibly made my shirt.

When Amilcar stopped to talk with me, the randomness and the silliness faded, replaced by awkwardness and questions from a forgotten sociology course: Does this job provide a better life for you and your family? What are you paid? Is this one of those sweatshops?

Of course, I didn't ask any of these questions. I think deep down I didn't really want to know. Amilcar and I were the same age, but our lives were vastly different. I was traveling on a whim, following my curiosity wherever it led, and he was working in the factory that made my T-shirt. I looked at myself through his eyes as I had once looked at myself through the eyes of a beggar in Nepal, and I saw the privileges and opportunities of my own life. I wrestled with the fact that people make the clothes we wear, and we have it made.

I went to Cambodia where my jeans were made and while there I met the girl. I wondered what life was like for her and other rural farmers who were leaving the fields for factories, and I traveled around the world to meet farmers. That's when I met Solo on the cocoa farm. One person, story, and question flowed into the next.

I'm privileged, but I'm not Batman's alter ego Bruce Wayne by any means. In the 16 years of travel covered in this book, at times I earned a poverty wage, once I was unemployed, but mostly I earned a solid, but very unpredictable, middle-class income. Yet I received an education. I have access to health care. I have not known hunger or war, nor have my wife and kids. There are privileges beyond financial ones. Being a straight, middle-class, able-bodied, white dude in Muncie, Indiana, certainly comes with its own privileges.

I've traveled to some of the poorest places on our planet, and there are people I wish I could forget, like the girl trash picker, Solo the slave, and Amilcar the garment worker, but I never will. These are people who live in circumstances that have often paralyzed me to the point of inaction. But from the very beginning, I began to feel the responsibility of my privilege, and of the opportunities in my life that I have, that you likely have, that most of the world's people don't.

This is something I've been struggling with for years.

My global searches for connection have inspired me to try to be a better giver, activist, and global and local citizen. They inspired me to cofound a community storytelling nonprofit, The Facing Project, which has engaged more than 200,000 people nationwide. But still, when I think about the girl and Solo and Amilcar, I feel like I'm not doing enough.

Awareness without action feels irresponsible. I believe I have a responsibility to act, to do something, and I believe you do as well. If you make $52,000 per year, you are in the top 1% of global earners. Even if you live on $11,000 per year, which is below the poverty line in the US, you are richer than 85% of the world's population.3 If you graduated from college, you are more educated than 90% of the rest of the world. If you are fortunate enough...

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.