Suchen und Finden

CHAPTER 1

Childhood

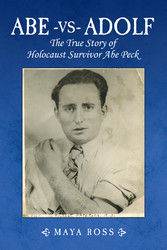

On November 25, 1924, an innocent child was born to adoring parents who had no idea their lives were doomed. The little boy, Abraham Pik, was well-cared for, nurtured and protected by his loving family and close-knit community. Until his teenage years, he lived a simple, happy life, engaging in normal everyday activities. Bright, studious, athletic and kind, he was just a regular kid going about his regular life. When his world ultimately shattered around him, it wasn’t because he had done anything wrong; his misfortune was being born in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Before World War II, Abe Pik1 had what most people would consider to be a delightful childhood. Growing up in Poland in the small town of Szadek (pronounced Shah-dek), thirty-seven kilometers from the city of Lodz (pronounced Loj), Abe had many good friends and was blessed to be surrounded by a large doting family. He loved to learn and did extremely well in school. In his free time he enjoyed many outdoor activities such as boating and sledding.

Abe clearly remembers his summer and winter pursuits, describing them with vivid recall as though it were yesterday: “Me and my best friend Monick built a kayak. We bent thin plywood. There were no staples then—we used nails. We put tar on it. It had one oar. In the winter we had sleds.”

He also has fond memories of swimming in a big lake near town—his father taught him how to swim—riding a bike—even though it was too big for him—and making his own telephone out of a shoe shine box and twine—which really worked!

“I was very happy.”

Daily Life

Growing up in Szadek, Abe did not have the benefit of the modern amenities that we take for granted today. His day-to-day lifestyle was quite primitive, a far cry from our present-day world replete with computers, smartphones, cable television, video game systems, and the Internet.

There were no toilets inside Abe’s home—they had to use an outhouse in the backyard. They had no running water—the water carrier would deliver their water in large buckets every day, sometimes twice a day. Baths were taken every second or third day in a round wooden tub with water warmed at the stove using wood and coal. The kitchen had no sink—they washed dishes in a special oval metal bin, similar to an oversized deep metal baking pan.

While the town of Szadek did have electric power in the 1930s, it was very limited. “There was only a few hours of electricity until 12 at night. At 11:30 p.m. the lights would blink and then shut off. People used lanterns outside. Inside, they used petroleum, called nafta, or candles.”

Abe’s family lived in a tiny home with only three rooms—a dining room, bedroom, and kitchen. His parents Hannah and Jacob slept in the bedroom while he and his sister Miriam shared the dining room. As Abe got older, his father hung a curtain across the dining room to give him and his sister more privacy.

During Abe’s childhood, cars were a luxury item which only the wealthy could afford. Like the Pik family, most of the townspeople of Szadek were too poor to own cars and got around on horse and buggy. “There was only one taxi in town owned by a doctor. The motor needed to be hand-cranked and when it first started up, the kids would run faster than the car.”

Abe explains the standard for being rich at that time: “Poland was a poor country. You were rich if your family ate meat two to three times a week. None of us were rich.”

Getting food in Szadek wasn’t as easy as running down to the local convenience store. Supermarkets did not exist and there were no grocery shops in town. To buy milk, people would make frequent trips to local farmers. Abe would go to a nearby farm every day or two toting a metal pail etched with one- and two-liter lines. “The farmer would milk the cow right into the pail. It had to be our pail to make sure it was kosher. My mother wasn’t religious but kept a kosher house only so her brothers—who were very religious—could eat at our house.”

Other dairy products like cheese, eggs and butter were purchased at a farmer’s market in town every Wednesday. At the market, the Piks would also buy fresh fruit, vegetables, eggs, chickens, turkeys, ducks, and doves. In addition, Abe’s father cultivated his own small garden in their yard. “My dad had planted green onions outside by the fence and would dump the dirty water on the vegetables.”

Abe’s father didn’t just grow vegetables for his family’s consumption. He owned a popular restaurant in town. “It was like a diner here. He served good things. We ate there once in a while. My father was an excellent cook. There was always turkey. People had dinner and lunch. We were not poor but not rich. We always had the necessities of life. I never remember going hungry to bed or not being clothed right.”

Both of Abe’s parents were intellectuals who stayed well-informed. “We had three or four newspapers every day. We had the Folkstsaytung [The People’s Paper] in Yiddish, and the Ekspres in Polish, plus two weekly papers. Me and my sister couldn’t wait to get the comics section from the Sunday papers.”

Abe and his sister knew both Polish and Yiddish because they spoke Yiddish at home and learned Polish in school. Both his parents were fluent in Polish, Yiddish, and Russian, and his mother was also proficient in German.

Religious Observance

Although Abe was not brought up in a religious household, many of his parents’ relatives from both sides of the family were devout followers of Judaism. His paternal grandfather, in particular, did not approve of Abe’s father’s lax attitude.

“Our house was not a strict religious house, but everyone went to shul [synagogue] on Shabbos [Sabbath]. I remember once when my father didn’t go and after services at noon my grandfather came over and said, ‘How come you didn’t go?’ He [my grandfather] didn’t like his answer and smacked my father in the face, in front of me. He [my father] had shamed the family. My father apologized for it.”

Abe’s parents may not have been very religious—like other Jews who went to temple three times a day, seven days a week—but they celebrated Jewish holidays and kept up Jewish traditions. Passover, in particular, was a joyous holiday which everyone observed, no matter how religious. “My grandfather made sure there was a traditional Seder—he put on a white robe. The young people skipped a lot. We had two sets of dishes, Passover [and regular] dishes. Where I came from, even the most liberal person observed Passover. Maybe they didn’t want to shame the family.”

Abe regularly attended Hebrew School to study the Bible and learn prayers. “After school I went every day for one to one-and-a-half hours to cheder [religious school] which was at a Rebbi’s [teacher’s] house.”

He also had a bar mitzvah, but it was not like any of the lavish affairs we see today. There were no DJs, dancers, or high-tech lighting. There was no ornate catering hall or extravagant smorgasbord topped off with a sundae bar and chocolate fountain. “In those days a bar mitzvah was very simple. The women made some food. There was petcha [called jallia in Yiddish, which is a cow’s leg that becomes the consistency of gelatin when cooked] and herring.”

Abe’s preparation for his bar mitzvah service was also minimal. Nowadays, kids who are approaching bar mitzvah age study far in advance and lead large portions of the Sabbath service, but expectations were quite different back when Abe became a bar mitzvah.

“I had a bar mitzvah in 1938. We postponed it because of weather. I said maftir [the concluding portion of the Torah service on the Sabbath] for that particular week. The rabbi checked me out once or twice and that was the end of it.”

Unfortunately, this otherwise happy occasion was overshadowed by the frightening predicament European Jews were facing at that juncture in history. Abe’s sunny disposition instantly darkens when he discusses what it was like to be a Jew in pre-WWII Europe as antisemitism intensified.

“We heard Hitler’s speeches on the radio. We got newspapers which reported what was happening in Germany. Hitler had been bad for Jews starting in 1933. He’d cleared very smart Jews from big and important positions in Germany. He’d made Jews close their businesses. It was a sad time. The Jewish people were depressed and worried at the time I became a bar mitzvah.”

Antisemitism2

Long before Hitler’s rise to power, antisemitism was always prevalent in Abe’s life. Starting at a very young age, he was exposed to the cruelty, ignorance, and intolerance of others.

Even though Abe’s parents were extraordinarily open-minded and free-thinking for their time, these admirable traits were not reflective of how others behaved. Abe reports that a deep-seated prejudice against Jews existed which made it difficult for him and his sister to befriend non-Jewish...

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.