Suchen und Finden

FOREWORD

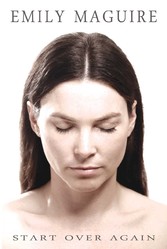

My name is Emily Maguire. I am an English singer-songwriter.

This is my story.

* * *

I was born in London in 1975. My dad will laugh at this because when I was a kid I was forever writing stories starting with a ‘foreword’ that would take up so much time and effort I’d run out of steam after chapter one. I also wrote diaries and sentimental poems that I never showed anyone, or I hope I didn’t. Growing up with my beloved older sister and without a TV at home, I developed a passion for books and music from an early age, learning to play the recorder, piano, flute and cello. I had a very happy childhood.

By the time I was 12, it seemed like I might become a professional cellist. But in my teens, family difficulties put me under a lot of stress and I left home at 16, dropped out of college and was diagnosed with acute clinical depression. Not wanting to get better, I refused any medication for 3 months until my psychiatrist threatened to section me in a psychiatric unit. I was living in a shared flat with strangers above a Cambridge shopping mall, having visions and writing desperate words on scraps of paper, suicidally depressed but too stoned to kill myself. I ate nothing but Crunchy Nut Cornflakes for months until my gums were bleeding constantly and my hair was falling out. I became obsessed with Bob Marley, playing his tapes over and over again. Finally I agreed to take the anti-depressants, which I remained on for the next 4 years, and slowly began to recover. I moved first to France to work in a hotel, then to London to live at my aunt’s house before returning back home to live with my mum and finish my A-levels in Cambridge in the autumn of 1992.

A year later, a car crash triggered a nervous system disorder called fibromyalgia pain syndrome (FMS) which became so acute over the next few years that I ended up on walking sticks, unable to work and stuck at home in a lot of pain for months on end. For my 21st birthday my mum gave me a guitar. I taught myself to play it from Bob Marley songbooks and a few months later a friend suggested I write a song. It was a complete revelation. I’d always loved poetry, and songwriting perfectly combined my love of words and music. Suddenly the illness became a complete blessing in disguise as I had all this time on my hands to write songs. I wrote constantly in my room, songs pouring out of my head, watching the sky outside my window. I smoked dope from morning to night, as a certain type of cannabis was the only thing that relieved the pain of muscle spasms caused by the FMS.

I tried everything to relieve the pain – cortisone steroid injections, magnets, TENS machine, aromatherapy, acupuncture, Chinese herbs, osteopathy, chiropractic, heat pads, yoga, Tai Chi, reiki, hydrotherapy… and every painkiller under the sun the doctor would prescribe me. Nothing helped except the cannabis, or diazepam, which I wasn’t allowed because of its psychotropic side-effects. My mum looked after me, helping me up the stairs, making me food, giving me baths, buying me one pain-relieving treatment after another, taking me to appointments with specialists and therapists who said they could help. I was in hospital 3 times at the Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases in Bath and on the third occasion, in 1996, I finally came to terms with the fact that my condition was permanent, and as far as anyone knew, incurable. I was 21 years old. In a moment of complete and utter despair, I sat in the garden of the hospital with my walking sticks, looked up at the night sky and felt a sudden feeling of warmth and joy, the words ‘I can, I can’ ringing in my ears.

In February 1998, after months of disability, I dislocated a rib and the pain went completely out of control. Every nerve in my body felt like it was on fire. The doctor prescribed me dihydracodeine which did nothing so I chain-smoked joints and drank valerian tea. Over the next few weeks, I began to see connections and coincidences and symbolism in everything. I stopped eating and sleeping, becoming ecstatically happy despite the pain, madly writing all the time, losing all inhibitions and thinking I was becoming enlightened. On my 23rd birthday, I was taken by ambulance to Fulbourn Mental Hospital in a psychosis.

When I came round days later, drugged up to the eyeballs and absolutely terrified, the doctors told me I had manic depression, or bipolar disorder as it’s now called. I had just had my first manic ‘episode’. They told me if I had another psychosis it might be more difficult to ‘bring me back’. I was kept on the acute ward in the hospital for 2 weeks. Frightened by the other patients, I was desperate to get out but unable to communicate with the doctors because the drugs they were giving me made me unable to speak properly. For years afterwards, I would have nightmares where I would be trying to convince a doctor I was sane but when I tried to speak my words would come out all jumbled and slurred.

Once I got out and was back in my room at home, it was a long road to recovery. Chronically depressed, anxious and unable to write songs, food and routine became obsessively important. I got my rib fixed, and started swimming every day. I refused to go to my outpatient psychiatric appointments, reasoning that 7 years of therapy since my first breakdown had landed me in the nuthouse so it clearly wasn’t working. But I felt I had to do something about my mind – to tame it. I couldn’t just rely on the drugs. So eventually, after reading ‘The Way To Freedom’ by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, I made an appointment to see my sister’s Buddhist teacher Lama Jampa Thaye in Manchester. He told me to do a simple breathing meditation for 5 minutes each day. At first 5 minutes seemed like half an hour but I soon got into the habit of doing it, and found that bit of space and silence first thing in the morning helped me feel calmer, clearer and better able to focus on the rest of the day.

After 6 months of writer’s block, I finally wrote ‘I Thought I Saw’, the only way I could express what had happened to me. A friend made me laugh when he asked me if it was a love song. A few months later, when I was feeling much stronger, I wrote ‘I’d Rather Be’. I moved in with my boyfriend in London where for the next few years I lived fairly happily on lithium. After nearly 10 years of constant pain, homeopathy helped me recover from the FMS and I even found the courage to start singing my songs in open-mic clubs. Strangely, despite all the classical concerts and competitions I’d done as a child playing the cello, I was terrified of singing my songs on stage. Forced by my great-uncle into singing my first song in public at the Square & Compass Inn in Dorset, I then sang 3 songs at the open-mic night at Cambridge Folk Club where a kind man changed my guitar string that was about to break (I’d never changed a string on my guitar before). I got a Tascam four-track recorder and started recording my songs.

In London, I went along to see a friend play at the open-mic night at The Half Moon in Putney just to check it out. There were about 20 people sitting at tables with candles and I thought I can do this, so I signed up for the next one. When I arrived on the night clutching my guitar, to my horror I discovered the room was rammed with about 150 people. It was someone’s birthday. I nearly died from fright on the spot. My old friend Doug Cooper, who’d been working with me recording my songs, said he aged about 10 years watching me do that gig. Shaking like a leaf, I staggered up on the stage and somehow managed to get through ‘Stranger Place’. All I could hear was talking and I was sure no-one was listening but when I played the last chord, there was this huge applause. I couldn’t believe it – they liked it!

I started doing gigs with a cellist and got some interest from BMG and a management team. It seemed like my music career was about to take off. I even managed to stop smoking at the Allen Carr clinic in London. But then the depression came back in 2002 after I got RSI from a typing job and couldn’t play my guitar for months. When my long-term relationship ended in November that year I had another psychotic breakdown and was sectioned at Park Royal Centre for Mental Health in London. I hadn’t slept for 5 days and had ended up in a church in Willesden Green being chased around by police, ambulance men and the caretaker who’d inadvertently let me in. Used to Buddhist shrine rooms where you take off your shoes, I yelled at the policeman for not taking his boots off in church. Eventually they caught me, and on arriving at the hospital in an ambulance, I was delighted to find God waiting for me in reception in the form of a big beautiful black woman who later turned out to be a nursing assistant called Rita.

The strange and twisted thing about psychosis is you remember everything. Well, nearly everything. Park Royal was a very different experience to Fulbourn. We were not drugged up to the eyeballs except at night. They let me keep my guitar with me on the acute ward and we’d sing endless Bob Marley songs in the smoking room. It was quite an experience singing ‘No Woman No Cry’ with five women, all mental patients, some with bandages on their wrists. One lady wrote a letter to the Queen on a clinical history sheet she’d nicked from the office, demanding that she make me a Fellow of the Royal College of Music. (She actually got a reply but never told me what it said.) I would introduce everyone to everyone and write their...

Alle Preise verstehen sich inklusive der gesetzlichen MwSt.